“Idleness is the beginning of all vice, the crown of all virtues.”

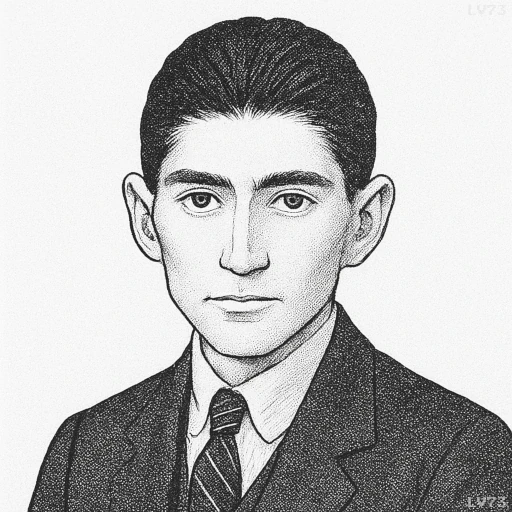

- July 3, 1883 – June 3, 1924

- Born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Writer, lawyer

table of contents

Quote

“Idleness is the beginning of all vice, the crown of all virtues.”

Explanation

In this provocative statement, Franz Kafka presents a paradoxical view on idleness, suggesting that it is both the origin of vice and the culmination of virtue. On one hand, idleness is described as the beginning of all vice, perhaps because inactivity or a lack of purpose can lead to negative emotions such as boredom, discontent, or restlessness, which may give rise to unproductive or even destructive behaviors. Kafka might be pointing to the way that empty time—when left unchecked—can breed a sense of frustration or dissatisfaction, pushing individuals to fill that space with vices or behaviors that offer temporary relief but ultimately lead to regret or loss. The association of idleness with vice may reflect Kafka’s recognition of the human tendency to fill idle moments with distractions or habits that pull us away from more meaningful engagement with life.

On the other hand, Kafka also claims that idleness is the crown of all virtues, suggesting that in some way, idleness can lead to enlightenment or wisdom. This counterintuitive statement implies that true virtue may be found not in constant action or striving, but in stillness—in the capacity to be present and at peace with oneself without the need for external validation or achievement. Kafka seems to be touching on a form of spiritual or existential transcendence, where idleness represents a freedom from the demands and expectations of the world. In this sense, idleness is not about doing nothing, but rather about accepting and embracing the moment as it is, free from the pressure of productive goals or social obligation. It suggests a type of virtue that can only arise when one is detached from the constant busyness and turmoil of life, and instead finds meaning and peace in simply being.

Kafka’s paradoxical view of idleness can be seen as a critique of modern life, which often emphasizes constant activity, productivity, and achievement as measures of value and success. In contemporary society, where the expectation to always be busy or doing is pervasive, Kafka’s insight offers a counterpoint: that perhaps stillness—even in the form of idleness—is essential for personal growth and self-understanding. In works like The Trial and The Castle, Kafka’s characters often find themselves trapped in systems that demand relentless action, yet this constant striving only deepens their alienation and sense of powerlessness. In contrast, true virtue might lie in the ability to step away from the compulsions of the world and recognize the deeper meaning of existence. In the quiet, unproductive moments, the soul can find clarity, acceptance, and freedom. Kafka’s words encourage us to rethink our relationship to idleness—not as a sign of failure or vice, but as a path to inner peace and a deeper connection with our true selves.

Would you like to share your impressions or related stories about this quote in the comments section?