“So long as you have food in your mouth, you have solved all questions for the time being.”

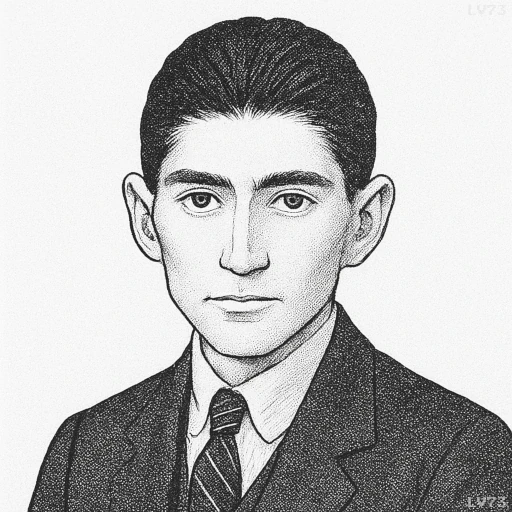

- July 3, 1883 – June 3, 1924

- Born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Writer, lawyer

table of contents

Quote

“So long as you have food in your mouth, you have solved all questions for the time being.”

Explanation

In this quote, Franz Kafka offers a stark reflection on the way basic survival can provide temporary relief from the broader, often overwhelming questions of life. The act of having food “in your mouth” is a metaphor for the immediate gratification of a fundamental need, suggesting that, when our most urgent survival needs are met, all other concerns—be they existential, philosophical, or emotional—seem to fade into the background. Kafka here seems to imply that comfort and security, even if only for a moment, have the power to suspend the deeper anxieties of life, such as the search for meaning, purpose, or understanding.

This quote touches on a recurring theme in Kafka’s works—the tension between material necessity and spiritual longing. Kafka often portrays his characters as being caught in a struggle between their physical survival and their psychological or existential burdens. In The Trial or The Metamorphosis, characters are weighed down by bureaucratic absurdities, alienation, or the need to find meaning in an otherwise indifferent world. For Kafka, the act of eating or consuming food may represent a brief respite from these overwhelming questions, a momentary escape from the absurdities of existence, where the mind is briefly satisfied by something concrete and immediate.

In a modern context, this quote resonates with the way instant gratification or basic comforts can sometimes offer temporary relief from the complexities of contemporary life. In a world where work, financial pressures, and social expectations often overwhelm the individual, Kafka suggests that even the most mundane or necessary acts, like eating, can temporarily shield us from the existential weight of our larger struggles. Yet, this fleeting sense of satisfaction also raises questions about the limitations of such relief—while food may temporarily silence the deeper questions of life, the moment inevitably passes, and we are left once again facing the uncertainty of existence. This paradox points to the fragility of human contentment and the way that comforts often mask the pervasive restlessness of the human condition.

Would you like to share your impressions or related stories about this quote in the comments section?