“Contempt is the eternal critique of a woman towards a man.”

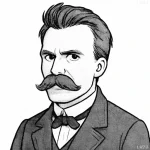

- January 14, 1925 – November 25, 1970

- Born in Japan

- Novelist, playwright, critic, political activist

Japanese

「軽蔑とは、女の男に対する永遠の批評なのであります」

English

“Contempt is the eternal critique of a woman towards a man.”

Explanation

In this quote, Mishima suggests that contempt is an inherent and everlasting critique that women direct towards men. He implies that, in the dynamics between the sexes, contempt functions as a constant or underlying judgment that women hold over men. This critique is not necessarily one of overt rejection but is a more subtle, ongoing evaluation of men’s actions, motives, or nature. In Mishima’s view, this contempt could be seen as a kind of unavoidable commentary on masculinity, pointing to the flaws or contradictions he perceives in the male gender. Mishima’s tone here hints at the complex relationships between the sexes, where women’s contempt becomes a form of psychological resistance or reaction to male behavior.

Mishima often explored the tensions between masculinity and femininity in his works, suggesting that the roles and perceptions of each are deeply interconnected and marked by conflict. His statement reflects his belief in the power dynamics between men and women, with women’s contempt representing an ongoing reflection of men’s failings or the dissatisfaction with male behavior. This critique from women could be seen as a counterbalance to the dominant masculine ideals of the time, offering a silent resistance or judgment that forces men to confront their own shortcomings.

In a modern context, this quote invites reflection on the gender dynamics that still persist in contemporary society. While contempt may not be expressed as openly or directly today, there are still underlying critiques of masculinity and femininity that shape relationships and societal roles. Mishima’s view encourages us to examine how gendered judgments—particularly those rooted in contempt—continue to influence the way men and women view one another. It also speaks to the complexity of gendered power dynamics, where women’s criticism of men may reflect deeper, more systematic inequalities or the frustrations of being subject to male-dominated structures. Ultimately, Mishima’s statement underscores the ongoing dialogue between men and women, marked by both cooperation and conflict, where contempt can serve as a powerful form of resistance and critique.

Would you like to share your impressions or related stories about this quote in the comments section?